The embryological basis for most neural tube defects is inhibition of closure of the neural folds at the cranial and caudal neuropores. In turn, defects occur in surrounding structures, resulting in anencephaly, some types of encephaloceles, and spina bifida cystica. Neural tube defects, which occur in approximately 1 in 1,500 births, may be diagnosed prenatally by ultrasound and findings of elevated levels of a-fetoprotein in maternal serum and amniotic fluid. Recent evidence has shown that daily supplements of 400 mg of folic acid started 3 months prior to conception prevent up to 70% of these defects. This condition, hydrocephalus, results from a blockage in the flow of cerebrospinal fluid from the lateral ventricles through the foramina of Monro and the cerebral aqueduct into the fourth ventricle and out into the subarachnoid space, where it would be resorbed. It may result from genetic causes (X-linked recessive) or viral infection (toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus). The autonomic nervous system is composed of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic portion has its preganglionic neurons located in the intermediate horn of the spinal cord from T1 to L2. The parasympathetic portion has a craniosacral 356 Answers to Problems origin with its preganglionic neurons in the brain and spinal cord (S2 to S4). A placode is a region of cuboidal ectoderm that thickens by assuming a columnar shape. The otic placodes form on both sides of the hindbrain and then invaginate to form otic vesicles. Thus, from the otic vesicle, tubular outpocketings form and differentiate into the saccule, utricle, semicircular canals, and the endolymphatic and cochlear ducts. Together, these structures constitute the membranous labyrinth of the internal ear. The tympanic (middle ear) cavity and auditory tube are derivatives of the first pharyngeal pouch and are lined by endoderm. The pouch expands laterally to incorporate the ear ossicles and create the middle ear cavity, while the medial portion lengthens to form the auditory tube that maintains an open connection to the pharynx. The tympanic membrane (eardrum) forms from tissue separating the first pharyngeal pouch from the first pharyngeal cleft. It is lined by endoderm internally and ectoderm externally with a thin layer of mesenchyme in the middle. Microtia involves defects of the external ear that range from small but well-formed ears to absence of the ear (anotia). Other defects occur in 20% to 40% of children with microtia or anotia, including the oculoauriculovertebral spectrum (hemifacial microsomia), in which case the craniofacial defects may be asymmetrical. Because the external ear is derived from hillocks on the first two pharyngeal arches, which are largely formed by neural crest cells, this cell population plays a role in most external ear malformations. The lens forms from a thickening of ectoderm (lens placode) adjacent to the optic cup. Lens induction may begin very early, but contact with the optic cup plays a role in this process as well as in maintenance and differentiation of the lens. Therefore, if the optic cup fails to contact the ectoderm or if the molecular and cellular signals essential for lens development are disrupted, a lens will not form. Rubella is known to cause cataracts, microphthalmia, congenital deafness, and cardiac malformations. Exposure during the fourth to eighth week places the offspring at risk for one or more of these birth defects. As the optic cup reaches the surface ectoderm, it invaginates, and along its ventral surface, it forms a fissure that extends along the optic stalk. It is through this fissure that the hyaloid artery reaches the inner chamber of the eye. Normally, the distal portion of the hyaloid artery degenerates, and the choroid fissure closes by fusion of its ridges. If they occur distally, they form colobomas of the iris; if they occur more proximally, they form colobomas of the retina, choroid, and optic nerve, depending on their extent. Also, mutations in this gene have been linked to renal defects and renal coloboma syndrome. Mammary gland formation begins as budding of epidermis into the underlying mesenchyme.

By the sixth week of embryogenesis, the prosencephalon differentiates into the telencephalon and diencephalon, the mesencephalon remains unchanged, and the rhombencephalon divides into the metencephalon and myelencephalon. Ultrasound images of the fetal brain at 7 to 8 weeks of gestation (menstrual age) demonstrate these brain vesicles. The falx cerebri, an echogenic structure that divides the brain into two equal halves, and the choroid plexuses, which fill the lateral ventricles, are seen on ultrasound by the end of the eighth week and beginning of the ninth week of gestation. The cerebellar hemispheres develop in the rhombencephalon and are completely formed by the 10th week of gestation, thus allowing for evaluation of the posterior fossa with optimal ultrasound imaging. Cranial ossification begins around the late 9th, early 10th week and is completed by the 12th week of gestation. Note the size of the rhombencephalic vesicle (Rb) in the posterior aspect of the brain as the largest brain vesicle at this stage of development. Note at 9 weeks of gestation (A), the presence of small islands of ossification (arrows). At 10 weeks of gestation (B), partial ossification of the frontal (F), parietal (P) and occipital (O) bones is seen. At 13 weeks of gestation (C), the frontal (F), parietal (P) and occipital (O) bones are clearly seen. The occipital bone (O) is better imaged in a more posterior plane at the level of basal ganglia. Furthermore, the midsagittal plane is also obtained for the evaluation of the fetal facial profile and nasal bones. The authors recommend routine evaluation of the axial and midsagittal planes of the fetal head when ultrasound examinations are performed beyond the 12 weeks of gestation. Axial Planes the systematic detailed examination of the fetal brain in the first trimester includes the acquisition of three axial planes, similar to the approach performed in the second trimester ultrasound examination. In these planes, the fetal head shape is oval and the skull can be identified from 10 weeks onward. At this early gestation, bone ossification primarily involves the frontal, parietal, and occipital parts of the cranial bones. The intracranial anatomy is divided by the falx cerebri into a right and left side of equal size. The choroid plexus on each side is hyperechoic, typically fills the lateral ventricles, and is surrounded by cerebral spinal fluid. In the first trimester, the shape of the choroid plexus is described to be similar to a butterfly. In an axial superior plane of the fetal head, a fluid rim can be seen surrounding the choroid plexus on each side, corresponding to the lateral ventricle. A more inferior axial plane toward the base of the skull shows the two thalami and the third ventricle, forming the diencephalon. Posterior to the thalami, the two small cerebral peduncles are identified surrounding the aqueduct of Sylvius and forming the mesencephalon (midbrain). The developing cerebellum is identified in the posterior fossa primarily by transvaginal ultrasound and in an axial plane that is tilted toward the upper spine. A slightly more inferior plane will show the fourth ventricle, the future cisterna magna, and the hyperechogenic choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle. The 3D volume was obtained from an axial plane and is displayed in tomographic view. Note the improved resolution in the transabdominal linear (B) and transvaginal (C) transducers. Note that at this stage of development, the ventricular system occupies the majority of the brain. Note in A to C the presence of choroid plexus asymmetry (double arrows), considered as a normal variant. The midsagittal plane reveals more anatomic intracranial information when examined from the ventral approach (fetus back down). In the context of spina bifida later in this chapter, the anatomy of the posterior fossa under normal and abnormal conditions is discussed. Coronal Planes the coronal planes of the fetal head are obtained along the laterolateral axis of the fetus. In the second and third trimesters, coronal planes of the fetal head are primarily obtained to assess the frontal midline structures such as the interhemispheric fissure, the cavum septi pellucidi, frontal horns of the lateral ventricles, the Sylvian fissure, the corpus callosum, and the optic chiasm. Given that these midline anatomic structures are not fully developed in the first trimester, coronal planes of the fetal head are rarely obtained.

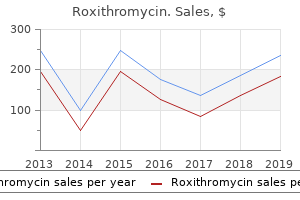

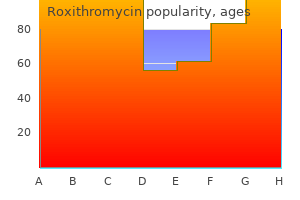

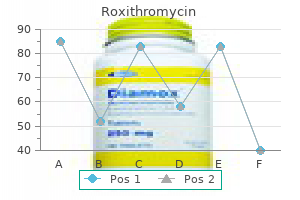

| Comparative prices of Roxithromycin | ||

| # | Retailer | Average price |

| 1 | Advance Auto Parts | 847 |

| 2 | Dell | 130 |

| 3 | WinCo Foods | 801 |

| 4 | Verizon Wireless | 738 |

| 5 | Abercrombie & Fitch | 570 |

| 6 | Raley's | 166 |

| 7 | TJX | 918 |

| 8 | Aldi | 287 |

Still others may be completely new to the subject, having picked up the book because they want to learn more about transsexuality, how to be a trans ally, or because they have a particular interest in the subjects of femininity and/or sexism. For me, it has certainly been a challenge to write a substantial book about such complex topics that can simultaneously be easily understood and enjoyed by audiences who so greatly differ in their prior knowledge and their presumptions. While I have written this book in "lay language" and with a general audience in mind, the use of transgender-specific or -related jargon is unavoidable. I have not only had to define a lot of preexisting terms for those who are new to this subject, but redefine or even create new terms to clear up confusion and to fill gaps left by the strange hodgepodge of clinical, academic, and activist language typically used to describe transgender people and experiences. While creating new terms can potentially be disconcerting to readers at first, I feel that it is necessary for addressing and challenging the many assumptions that are commonly made about gender and trans women. It is followed by Part 1, Trans/Gender Theory, which focuses largely on depictions and representations of transsexuals in the media, medicine and psychiatry, social sciences, academic gender studies, and queer and feminist politics. Because transsexuals make up a relatively small percentage of the population and have little to no power or voice in these fields, non-transsexual depictions regularly stand in for or trump the perspectives and experiences of actual transsexuals. This is highly problematic, as many of these depictions are sensationalizing, sexualizing, and/or outright hostile. This forces transsexuals to describe ourselves and our experiences in terms of non-trans terminology and values, which inevitably place us in a subordinate position. This also has the rather dubious consequence of positioning non-trans people who merely study transsexuality as "experts" who somehow understand transsexuals better than we understand ourselves. Of course, it is impossible to discuss such issues without having to grapple with another gender binary of sorts-that between gender essentialists (who believe that women and men represent two mutually exclusive categories, each born with certain inherent, nonoverlapping traits) and social constructionists (who believe that gender differences are primarily or exclusively the result of socialization and binary gender norms). For this reason, I have included my own view of gender in this section, one that accommodates my experiences both as a trans person and as a practicing biologist; one that acknowledges that both intrinsic and extrinsic factors help to shape the way that we come to experience and understand our own genders. Part 2, Trans Women, Femininity, and Feminism, brings together my experiences and observations-pre-, during, and post-transition-to discuss the many ways fear, suspicion, and dismissiveness toward femininity shape societal attitudes toward trans women and influence the way trans women often come to view ourselves. In the last two chapters of this section, I bring together several of the main themes in this book to suggest new directions for gender-based activism. In chapter 19, "Putting the Feminine Back into Feminism," I make the case that feminist activism and theory would be best served by working to empower and embrace femininity, rather than eschewing or deriding it, as it often has in the past. Such an approach would allow feminism to both incorporate transgender perspectives and reach out to the countless feminine-identified women who have felt alienated by the movement in the past. I argue that, rather than focusing on "shattering the gender binary"-a strategy that invariably pits genderconforming and non-gender-conforming people against one another-we work to challenge all forms of gender entitlement. For the purposes of this manifesto, trans woman is defined as any person who was assigned a male sex at birth, but who identifies as and/or lives as a woman. As a group, we have been systematically pathologized by the medical and psychological establishment, sensationalized and ridiculed by the media, marginalized by mainstream lesbian and gay organizations, dismissed by certain segments of the feminist community, and, in too many instances, been made the victims of violence at the hands of men who feel that we somehow threaten their masculinity and heterosexuality. Rather than being given the opportunity to speak for ourselves on the very issues that affect our own lives, trans women are instead treated more like research subjects: Others place us under their microscopes, dissect our lives, and assign motivations and desires to us that validate their own theories and agendas regarding gender and sexuality. Trans women are so ridiculed and despised because we are uniquely positioned at the intersection of multiple binary gender-based forms of prejudice: transphobia, cissexism, and misogyny. Transphobia is an irrational fear of, aversion to , or discrimination against people whose gendered identities, appearances, or behaviors deviate from societal norms. The fact that transphobia is so rampant in our society reflects the reality that we place an extraordinary amount of pressure on individuals to conform to all of the expectations, restrictions, assumptions, and privileges associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. Common examples include purposeful misuse of pronouns or insisting that the trans person use a different public restroom. There is no such thing as a "real" gender-there is only the gender we experience ourselves as and the gender we perceive others to be. While often different in practice, cissexism, transphobia, and homophobia are all rooted in oppositional sexism, which is the belief that female and male are rigid, mutually exclusive categories, each possessing a unique and nonoverlapping set of attributes, aptitudes, abilities, and desires. Oppositional sexists attempt to punish or dismiss those of us who fall outside of gender or sexual norms because our existence threatens the idea that women and men are "opposite" sexes. This explains why bisexuals, lesbians, gays, transsexuals, and other transgender people-who may experience their genders and sexualities in very different ways-are so often confused or lumped into the same category.

In addition, only a few of the pub lished reports provide information on the threshold field strengths needed to initiate inactivation. For pasteurization purposes, one is mostly concerned with the inactivation of vegetative cells of disease-producing microorgan isms. However, to have a commercially sterile product, the pro cess must control or inactivate any microbial life (usually target ing spores of Clostridium botulinum) capable of germinating and growing in the food under normal storage conditions. Efficacy of any preservation technology is influenced by a number of microorganism-related factors that are generally in dependent of the technology itself. Each influences the resis tance independently of the apparent inactivation capacity of that particular process. Extreme environments may select for forms resistant to severe conditions leading to a microbial population of greater resistance. An example of this is the higher heat resistance of acid- or salt adapted, heat-shocked or starved E. The ques tions relative to process design and verification are: (1) are the mi croorganisms and food environments likely to result in stress in duction Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora are protozoa of concern mainly because they produce resistant cysts. When exploring the new preservation technologies, their preservation level should be compared to that of classical pasteurization or commercial sterilization technologies. Establishment of traditional thermal processes for foods has been based on 2 main factors: 1) knowledge of the thermal inac tivation kinetics of the most heat-resistant pathogen of concern for each specific food product, and 2) determination of the na ture of heat transfer properties of the food system. Validity of the established process is often confirmed using an inoculated test pack study tested under actual plant conditions using surrogate microorganisms as biological indicators that can mimic the pathogen. Thus, the 2 factors described above, which are well es tablished for thermal processes, should be used for establishing and validating scheduled electrothermal processes. For other preservation processes not based on heat inactiva tion, key pathogens of concern and nonpathogenic surrogates need to be identified and their significance evaluated. Surro gates are selected from the population of well-known organisms that have well-defined characteristics and a long history of being nonpathogenic. Surrogates need to be nonpathogenic organisms and not susceptible to injury, with nonreversible thermal or other inactivation characteristics that can be used to predict those of the target organism. The durability to food and processing pa rameters should be similar to the target organism. Population of surrogates should be constant and have stable thermal and growth characteristics from batch to batch. Enumeration of sur rogates should be rapid and with inexpensive detection systems that easily differentiate them from natural flora. It is recommended also that surrogates do not establish themselves as "spoilage" organisms on equipment or in the production area. The validation process should be designed so that the surrogate exhibits a predictable time-temperature process character pro file that correlates to that of the target pathogen. Introduction of system modifications or variables, leading to inaccurate results. Microwave And Radio Frequency Processing use of electromagnetic waves of certain frequencies to gen erate heat in a material through 2 mechanisms-dielectric and ionic. Microwave and radio frequency heating for pasteurization and sterilization are preferred to conventional heating because they require less time to come up to the desired process temper ature, particularly for solid and semisolid foods. Industrial micro wave pasteurization and sterilization systems have been report ed on and off for over 30 y, but commercial radio frequency heat ing systems for the purpose of food pasteurization or sterilization are not known to be in use. For a microwave sterilization process, unlike conventional heating, the design of the equipment can dramatically influence the critical process parameter-the location and temperature of the coldest point. This uncertainty makes it more difficult to make general conclusions about processes, process deviations and how to handle deviations. The critical process factor when combining conven tional heating and microwave or any other novel processes would most likely remain the temperature of the food at the cold point, primarily due to the complexity of the energy absorption and heat transfer processes. Ohmic heating is distinguished applied in the form of exponentially decaying, square wave, bi from other electrical heating methods by the presence of elec polar, or oscillatory pulses and at ambient, sub-ambient, or trodes contacting the food, frequency, and waveform. Energy loss Inductive heating is a process wherein electric currents are in due to heating of foods is minimized, reducing the detrimental duced within the food due to oscillating electromagnetic fields changes of the sensory and physical properties of foods.

In a scanning electron micrograph, crest cells at the top of the closed neural tube can be seen migrating away from this area. These cells leave the crests of the neural folds prior to neural tube closure and migrate to form structures in the face and neck (blue area). Subcutaneous glands, the mammary glands, the pituitary gland, And enamel of the teeth. A B C Chapter 6 Third to Eighth Weeks: the Embryonic Period 71 Notochord Amniotic cavity Ectoderm Mesoderm Paraxial mesoderm Intermediate mesoderm Intercellular cavities in lateral plate Dorsal aorta A Amnion Neural groove Parietal mesoderm layer B Intermediate mesoderm Somite Visceral mesoderm layer Intraembryonic body cavity Endoderm C D Figure 6. The thin mesodermal sheet gives rise to paraxial mesoderm (future somites), intermediate mesoderm (future excretory units), and the lateral plate, which is split into parietal and visceral mesoderm layers lining the intraembryonic cavity. The first pair of somites Somite arises in the occipital region of the embryo at approximately the 20th day of development. There are 4 occipital, 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 8 to 10 coccygeal pairs. The first occipital and the last five to seven coccygeal somites later disappear, while the remaining somites form the axial skeleton (see Chapter 10). Because somites appear with a specified periodicity, the age of an embryo can be accurately determined during this early time period by counting somites (Table 6. Molecular Regulation of Somite Formation Formation of segmented somites from unsegmented presomitic (paraxial) mesoderm. Thus, Notch protein accumulates in presomitic mesoderm destined to form the next somite and then decreases as that somite is established. The increase in Notch protein activates other segment-patterning genes that establish the somite. Somite Differentiation When somites first form from presomitic mesoderm, they exist as a ball of mesoderm (fibroblast-like) cells. These cells then undergo a process of epithelization and arrange themselves in a donut shape around a small lumen. By the beginning of the fourth week, cells in the ventral and medial walls of the somite lose their epithelial characteristics, become mesenchymal (fibroblast-like) again, and shift their position to surround the neural tube and notochord. Collectively, these cells form the sclerotome that will differentiate into the vertebrae and ribs (see Chapter 10). Cells at the dorsomedial and ventrolateral edges of the upper region of the somite form precursors for muscle cells, while cells between these two groups form the dermatome. Cells from both muscle precursor groups become mesenchymal again and migrate beneath the dermatome to create Neural tube Ectoderm Somites Presomites mesoderm Figure 6. Somites form from unsegmented presomitic paraxial mesoderm caudally and become segmented in more cranially positioned regions. In addition, cells from the ventrolateral edge migrate into the parietal layer of lateral plate mesoderm to form most of the musculature for the body wall (external and internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles) and most of the limb muscles. Cells in the dermomyotome ultimately form dermis for the skin of the back and muscles for the back, body wall (intercostal muscles), and some limb muscles (see Chapter 11). Each myotome and dermatome retains its innervation from its segment of origin, no matter where the cells migrate. Hence, each somite forms its own sclerotome (the tendon cartilage and bone component), its own myotome (providing the segmental muscle component), and its own dermatome, which forms the dermis of the back. Molecular Regulation of Somite Differentiation Signals for somite differentiation arise from surrounding structures, including the notochord, neural tube, epidermis, and lateral plate mesoderm. Intermediate Mesoderm Intermediate mesoderm, which temporarily connects paraxial mesoderm with the lateral plate. In cervical and upper thoracic regions, it forms segmental cell clusters (future nephrotomes), whereas more caudally, it forms an unsegmented mass of tissue, the nephrogenic cord. Excretory units of the urinary system and the gonads develop from this partly segmented, partly unsegmented intermediate mesoderm (see Chapter 16). Lateral Plate Mesoderm Lateral plate mesoderm splits into parietal (somatic) and visceral (splanchnic) layers, which line the intraembryonic cavity and surround the organs, respectively.

Syndromes

Each referral letter, however, is expected to cover the same topics in the areas outlined below. Tasks Related to Psychotherapy Psychotherapy Is Not an Absolute Requirement for Hormone Therapy and Surgery A mental health screening and/or assessment as outlined above is needed for referral to hormonal and surgical treatments for gender dysphoria. Second, mental health professionals can offer important support to clients throughout all phases of exploration of gender identity, gender expression, and possible transition-not just prior to any possible medical interventions. Typically, the overarching treatment goal is to help transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming individuals achieve long-term comfort in their gender identity expression, with realistic chances for success in their relationships, education, and work. For transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming individuals who plan to change gender roles permanently and make a social gender role transition, mental health professionals can facilitate the development of an individualized plan with specific goals and timelines. Many transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming people will present for care without ever having been related to , or accepted in, the gender role that is most congruent with their gender identity. Other transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming individuals will present for care already having acquired experience (minimal, moderate, or extensive) living in a gender role that differs from that associated with their birth-assigned sex. Family Therapy or Support for Family Members Decisions about changes in gender role and medical interventions for gender dysphoria have implications for, not only clients, but also their families (Emerson & Rosenfeld, 1996; Fraser, 2009a; Lev, 2004). Family therapy may include work with spouses or partners, as well Appx250 Case: 17-1460 Document: 126 Coleman et al. For example, they may want to explore their sexuality and intimacy-related concerns. Alternatively, referrals can be made to other therapists with relevant expertise for working with family members or to sources of peer support. A more thorough description of the potential uses, processes, and ethical concerns related to e-therapy has been published (Fraser, 2009b). Other Tasks of the Mental Health Professionals Educate and Advocate on Behalf of Clients Within Their Community (Schools, Workplaces, Other Organizations) and Assist Clients with Making Changes in Identity Documents Transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming people may face challenges in their professional, educational, and other types of settings as they actualize their gender identity and expression (Lev, 2004, 2009). Mental health professionals can play an important role by educating people in these settings regarding gender nonconformity and by advocating on behalf of their clients (Currah, Juang, & Minter, 2006; Currah & Minter, 2000). This role may involve consultation with school counselors, teachers, and administrators, human resources staff, personnel managers and employers, and representatives from other organizations and institutions. E-therapy, Online Counseling, or Distance Counseling Online or e-therapy has been shown to be particularly useful for people who have difficulty accessing competent in-person psychotherapeutic treatment and who may experience isolation and stigma (Derrig-Palumbo & Zeine, 2005; Fenichel et al. By extrapolation, e-therapy may be a useful modality for psychotherapy with transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people. Telemedicine guidelines are clear in some disciplines in some parts of the United States (Fraser, 2009b; Maheu, Pulier, Wilhelm, McMenamin, & Brown-Connolly, 2005) but not all; the international situation is even less well defined (Maheu et al. Until sufficient evidence-based data on this use of e-therapy is available, caution in its use is advised. Both experiences are potentially valuable, and all people exploring gender issues should be encouraged to participate in community activities, if possible. Forms of distress that cause people to seek professional assistance in any culture are understood and classified by people in terms that are products of their own cultures (Frank & Frank, 1993). Cultural settings also largely determine how such conditions are understood by mental health professionals. Providing mental health care from a distance through the use of technology may be one way to improve access (Fraser, 2009b). In many places around the world, access to health care for transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people is also limited by a lack of health insurance or other means to pay for needed care. When faced with a client who is unable to access services, referral to available peer-support resources (offline and online) is recommended. If mental health professionals are uncomfortable with, or inexperienced in, working with transsexual, transgender, and gendernonconforming individuals and their families, they should refer clients to a competent provider or, at minimum, consult with an expert peer. Some people seek a maximum feminization/ masculinization, while others experience relief with an androgynous presentation resulting from hormonal minimization of existing secondary sex characteristics (Factor & Rothblum, 2008). Evidence for the psychosocial outcomes of hormone therapy is summarized in Appendix D. Hormone therapy can provide significant comfort to patients who do not wish to make a social gender role transition or undergo surgery, or who are unable to do so (Meyer, 2009). A referral is required from the mental health professional who performed the assessment, unless the assessment was done by a hormone provider who is also qualified in this area. If significant medical or mental health concerns are present, they must be reasonably well-controlled. Examples include facilitating the provision of monitored therapy using hormones of known quality as an alternative to illicit or unsupervised hormone use or to patients who have already established themselves in their affirmed gender and who have a history of prior hormone use.

It may be caused by a posterosuperior impact or be secondary to traction of xed tendinous bres on the surface of the largest tubercle. Liquid is present in the acromion-clavicular joint (Geyser sign) only when the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa is connected to the acromion-clavicular joint. A periarticular cyst is formed, secondary to the passage of the glenohumeral to the acromion-clavicular joint through rupture of the rotator cu. Liquid in the glenohumeral joint is identi ed either from distension of synovial recesses of the joint or from the amount of uid accumulated in the synovial sheath 420. In general, the synovial recesses are posterior, easy to access and located anterior to the tendinous muscle of the infraspinatus. Liquid accumulation occurs when the distance between the glenoid posterior labrum and the infraspinatus tendon is > 2 mm. External rotation during dynamic testing increases the sensitivity of the examination. Liquid in the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa is suspected when the bursa presents a thickness > 1. Although this phenomenon may also be seen in asymptomatic people, ultrasonographic detection of uid in the bursa and the glenohumeral joint is highly speci c for predicting rupture of the rotator cu. It is generated by posterior acoustic reinforcement due to the echoic rupture. Appropriate treatment should be based on an understanding of the type and dimensions of the tendinous rupture, the appearance of the glenohumeral joint on simple X-ray, the degree of muscle atrophy of the rotator cu and the case history. In the periolecranon area, three synovial bursae can be identi ed, one subcutaneous, one intratendinous and one between the elbow joint capsule and the brachial triceps tendon. A hypovascularized area is seen close to the insertion, and the presence of tendinopathy is common. Two synovial bursae are found in the area: the bicipitoradial, between the radius and the brachial biceps tendon, close to its insertion, and the interosseous, between the ulna and the brachial biceps tendon. Lateral and medial epicondylitis are overuse syndromes characterized by pain and increased sensitivity of the epicondyles, generally related to tendinopathy. It is the extensor compartment most frequently involved in stenosing tenosynovitis (De Quervain tenosynovitis;. Clinical examination reveals pain during palpation of the radial border of the wrist, and it may be di cult to di erentiate from thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis in the initial stages. Sonography: star, tuber of Lister; 1, long abductor tendons and short extensor of the thumb; 2, radial extensor tendons of the carpus; 3, long extensor tendon of the thumb; 4, extensor tendons of the ngers; 5, extensor tendon of the fth nger; 6, ulnar extensor tendon of the carpus a b c * d e second compartment contains the short and long radial extensor tendons of the carpus in the anatomical snu ox. It borders the anatomical snu box medially, passing over the radial extensor tendons (posterior) and inserts into the dorsal region of the distal phalange at the base of the thumb. A central tendon is inserted in the base of the medium phalanx on its dorsal face. Two tendinous bands meet near the base of the distal phalanx, medially and laterally to this tendon, forming the terminal tendon. Narrow strips of collagen, known as sagittal bands, link these structures to provide stability and allow harmonious extension. In its distal course, it divides into two bands, with insertion in the medial phalanx posterior to the exor digitorum profundus, which runs to the base of the distal phalanx. In contrast to the extensor apparatus, the exor tendons have a synovial sheath all along the phalanges. In cases of tenosynovitis, there may be some parietal thickening, uid or increased ow in the synovial sheath on colour Doppler. Adjacent to the tendons, three synovial bursae are seen: the trochanteric bursa, the bursa of the subgluteus minimus and the bursa of the subgluteus medius. One of the main causes is tendinopathy of the glutei and trochanteric bursitis. Longitudinal scans of the (c) gluteus minima tendon (arrow) and (d) the gluteus media tendon (arrow), with forms and echogenicity similar to that of the rotator cu tendons of the shoulder.

Musculature of the first pharyngeal arch includes the muscles of mastication (temporalis, masseter, and pterygoids), anterior belly of the digastric, mylohyoid, tensor tympani, and tensor palatini. The nerve supply to the muscles of the first arch is provided by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve. Since mesenchyme from the first arch also contributes to the dermis of the face, sensory supply to the skin of the face is provided by ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve. Muscles of the arches do not always attach to the bony or cartilaginous components of their own arch but sometimes migrate into surrounding regions. Nevertheless, the origin of these muscles can always be traced, since their nerve supply is derived from the arch of origin. Muscles of the hyoid arch are the stapedius, stylohyoid, posterior belly of the digastric, auricular, and muscles of facial expression. Third Pharyngeal Arch the cartilage of the third pharyngeal arch produces the lower part of the body and greater horn of the hyoid bone. These muscles are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve, the nerve of the third arch. Lateral view of the head and neck region demonstrating the cartilages of the pharyngeal arches participating in formation of the bones of the face and neck. Fourth and Sixth Pharyngeal Arches Cartilaginous components of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches fuse to form the thyroid, cricoid, arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform cartilages of the larynx. Muscles of the fourth arch (cricothyroid, levator palatini, and constrictors of the pharynx) are innervated by the superior laryngeal branch of the vagus, the nerve of the fourth arch. Intrinsic muscles of the larynx are supplied by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus, the nerve of the sixth arch. Since the epithelial endodermal lining of the pouches gives rise to a number of important organs, the fate of each pouch is discussed separately. First Pharyngeal Pouch the first pharyngeal pouch forms a stalk-like diverticulum, the tubotympanic recess, which comes in contact with the epithelial lining of the first pharyngeal cleft, the future external auditory meatus. The second arch grows over the third and fourth arches, burying the second, third, and fourth pharyngeal clefts. Remnants of the second, third, and fourth pharyngeal clefts form the cervical sinus, which is normally obliterated. The lining of the tympanic cavity later aids in formation of the tympanic membrane or eardrum (see Chapter 19). Second Pharyngeal Pouch the epithelial lining of the second pharyngeal pouch proliferates and forms buds that penetrate into the surrounding mesenchyme. The buds are secondarily invaded by mesodermal tissue, forming the primordium of the palatine tonsils. In the young child, the thymus occupies considerable space in the thorax and lies behind the sternum and anterior to the pericardium and great vessels. In older persons, it is difficult to recognize, since it is atrophied and replaced by fatty tissue. The parathyroid tissue of the third pouch finally comes to rest on the dorsal surface of the thyroid gland and forms the inferior parathyroid gland. Third Pharyngeal Pouch the third and fourth pouches are characterized at their distal extremity by a dorsal and a ventral wing. In the fifth week, epithelium of the dorsal region of the third pouch differentiates into the inferior parathyroid gland, while the ventral region forms the thymus. Both gland primordia lose their connection with the pharyngeal wall, and the thymus then migrates in a caudal and a medial direction, pulling the inferior parathyroid with it. Although the main portion of the thymus moves rapidly to its final position in the anterior part of the thorax, where it fuses with its counterpart from the opposite Fourth Pharyngeal Pouch Epithelium of the dorsal region of the fourth pharyngeal pouch forms the superior parathyroid gland. When the parathyroid gland loses contact with the wall of the pharynx, it attaches itself to the dorsal surface of the caudally migrating thyroid as the superior parathyroid gland. The ventral region of the fourth pouch gives rise to the ultimobranchial body, which is later incorporated into the thyroid gland. Cells of the ultimobranchial body give rise to the parafollicular, or C, cells of the thyroid gland. These cells secrete calcitonin, a hormone involved in regulation of the calcium level in the blood (Table 17. Primitive tympanic cavity External auditory meatus Palatine tonsil Superior parathyroid gland (from 4th pouch) Inferior parathyroid gland (from 3rd pouch) Ultimobranchial body Auditory tube Ventral side of pharynx Foramen cecum Thyroid gland Thymus Foregut Figure 17. The thyroid gland originates in the midline at the level of the foramen cecum and descends to the level of the first tracheal rings.

The precursors of various types of blood cells are generally regarded as being of mesodermal in origin. At a site where cartilage is to be formed, mesenchymal cells become closely packed. The mesenchymal cells then become rounded and get converted into cartilage forming cells or chondroblasts. Under the influence of chondroblasts, the intercellular substance of cartilage is laid down. Some chondroblasts get imprisoned within the substance of this developing cartilage and are called chondrocytes. In some situations, the intercellular substance is permeated by elastic fibers, forming elastic cartilage. In the compact bone the great majority of lamellae are arranged concentrically around longitudinal vascular channels within the bone to form cylindrical structure called Haversian system. They are large multinucleated cells and are seen in regions where bone is being absorbed. Both involve transformation of a pre-existing mesenchymal model of tissue into bone tissue. M e s e n c h y m a l c o n d e n s a i o n: St a r-s h a p e d mesenchymal cells of loose connective tissue aggregate in the area where bone is to be formed. The mesenchymal cells are converted to spindle-shaped cells thus forming a condensed mesenchymal tissue model. Conversion into a fibrous membrane: Spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells differentiate into fibroblasts. Fibroblasts lay down collagen fibers converting the mesenchymal model into a fibrous model. Osteoblast and osteoid formation: Fibroblasts get converted into osteoblasts and start laying down the early bone matrix, i. Mineralization of osteoid: Secretion of alkaline phosphatase by osteoblasts and deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals of calcium converts the osteoid into calcified bone matrix. Conversion of osteoblast to osteocyte and formation of woven bone: the osteoblasts trapped in matrix lacunae (shell around the bone cell) become osteocytes. Processes of osteoblasts traverse through mineralized canals of calcified matrix (tunnels) called canaliculi. The collagen fiber bundles run in different directions giving the appearance of a woven bone. Progressive bone formation: Fusion of adjacent spicules forms the bone model. Remodeling into lamellar bone: Woven bone gets transformed into lamellar bone due to resorption by osteoclasts and bone deposition by osteoblasts. In most parts of the embryo, bone formation is preceded by the formation of a cartilaginous model that closely resembles the bone to be formed. This type of ossification is seen in all long bones except clavicle, bones of base of skull, vertebrae and ribs. The essential steps in the formation of bone by endochondral ossification are (Flowchart 7. Mesenchymal condensation: At the site where the bone is to be formed, the mesenchymal cells become closely packed to form a mesenchymal condensation (Figs 7. Cartilaginous model: Some mesenchymal cells become chondroblasts and lay down hyaline cartilage. Mesenchymal cells on the surface of the cartilage form a membrane called the perichondrium. Cartilage cell hypertrophy: the cells of the cartilage are at first small and irregularly arranged. However, in the area where bone formation is to begin, the cells enlarge considerably. The nutrition to the cells is thus cut off and they die, leaving behind empty spaces called primary areolae (Figs 7. Vascularization of cartilaginous matrix: Some blood vessels of the perichondrium (which may be called periosteum as soon as bone is formed) now invade the calcified cartilaginous matrix.

Intra-abdominal tumours should be sought; in particular, both adrenal glands should be examined for a phaeochromocytoma, which can be located anywhere in the abdomen or pelvis. Screening for congenital renal abnormalities Ultrasound is the most e cient tool for identifying congenital intra-abdominal anomalies associated with various syndromes. Pelvis Indications Ultrasound remains the imaging modality of choice for initial evaluation of most abnormalities of the paediatric female pelvis. Examination technique e examination is usually carried out with the child in a supine position. A coupling agent is used to ensure good acoustic contact between the probe and the skin. Longitudinal scans are conducted, rst in the midline between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis and then more laterally, on the le and right sides. If necessary, the child is turned to the oblique position for identi cation of the ovaries. Normal ndings Uterus e size and appearance of the uterus vary with age and pubertal status. Longitudinal scan shows a prominent cervix and a thin, echo-rich endometrial stripe (arrowheads). Longitudinal scan shows a small, tubular uterus with no di erentiation between the fundus and the cervix and no recognizable endometrial stripe 316. Longitudinal scan shows a pearshaped uterus with a fundus that is larger than the cervix and an identi able central endometrial stripe (arrowheads) Ovaries e ovaries, like the uterus, change in size and morphology with age and pubertal status. A er the neonatal period, the ovarian volume decreases with the decrease in maternal hormone levels. From around 8 years of age, with the onset of puberty, the size of the ovary increases by at least four times. Longitudinal scan shows a large ovarian volume with multiple large follicles (arrows). Longitudinal scan shows multiple small follicles (arrows) < 9 mm in diameter and an ovarian volume of 2 cm3 318. Longitudinal scan of the right ovary shows a large ovary with multiple stimulated (arrow) and unstimulated (arrowheads) follicles Pathological ndings Ovarian masses Ultrasound is the initial imaging modality used in the diagnosis of suspected ovarian masses in children or adolescents. Ovarian cysts Functional ovarian cysts are the commonest cause of ovarian masses and have a bimodal age distribution, in neonates and adolescent girls. Functional ovarian cysts are o en asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally on pelvic ultrasound performed for other reasons. On sonography, the classical cyst is echo-free, with a sharp back wall and excellent through-transmission. Longitudinal scan shows a large echo-free cyst (c) with an imperceptible wall arising from the right ovary; B, bladder, U, uterus 319 Paediatric ultrasound conservatively and resolve spontaneously. Rarely, there are complications, such as ovarian torsion, haemorrhagic cyst or ruptured cyst.

References: