If the patient has a pathological fracture, surgical stabilization should be performed. Although surgical stabilization will often produce good pain relief, post-operative radiotherapy is recommended to gain tumour shrinkage and facilitate bone healing. Bisphosphonates Bisphosphonates are drugs which reduce osteoclast activity in bone metastases and reduce calcium resorption from the bone. They have a major role in treating hypercalcaemia, but have also been shown to reduce the risk of complications (pathological fractures, spinal cord compression and bone pain) in patients with bone metastasis. They are not useful in treating fracture risk or spinal cord compression, but are a useful follow-up treatment after palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases. Bone-seeking radioisotopes and hemibody radiotherapy Bone-seeking radioisotopes such as strontium-89 and samarium-153 are selectively taken up at sites of osteoblastic activity, where they are retained and deliver a significant dose of beta irradiation to a metastasis at that site. It is suitable for a selected group of patients with multiple sites of pain from osteoblastic bone metastasis (predominantly metastatic prostate cancer and some breast cancer metastases). The main toxicity is bone marrow depression, which may limit the scope for repeat treatment [23. Hemibody radiotherapy is also an effective treatment for multiple sites of pain from widespread bone metastasis. This is a single dose of radiotherapy given to the upper or lower half of the body. The response rate to hemibody radiotherapy and the duration of benefit are similar to those obtained with radioisotopes. Brain metastasis Brain metastases cause neurological symptoms, raised intracranial pressure and severe disability. Treatment options include corticosteroids, whole brain radiotherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, stereotactic radiosurgery and surgical resection. The median survival for a patient with brain metastasis varies from one month to several years, depending on the primary cancer, the extent of neurological deficit at diagnosis and the extent of metastatic disease outside the brain. For the most common clinical presentation of multiple brain metastasis, corticosteroids will provide short term symptom relief. A short course of whole brain irradiation will consolidate and maintain this symptom relief, with improvement in neurological function for a reasonable period of time [23. For patients with a solitary metastasis and no extracranial cancer, surgical excision with or without radiotherapy should be considered. Obstruction/compression symptoms A range of different symptoms arise when a cancer mass within or around a hollow organ causes compression or obstruction. Examples are: (a) (b) 366 Airway obstruction from bronchogenic carcinoma; Dysphagia from oesophageal cancer; (c) (d) (e) Superior vena cava obstruction; Urinary outlet obstruction; Spinal cord compression. As cancer shrinkage is required to achieve reliable and durable symptom relief, more fractionated palliative treatment regimes are preferred. Locally advanced lung cancer has been extensively studied: there is a trend towards improved survival and decreased re-treatment in biological equivalent doses of 35 Gy or higher. When higher dose treatment regimes are used, more advanced treatment techniques are justified to lessen treatment toxicity and achieve optimum quality of life. Bleeding, tumour ulceration and fungation Bleeding from a cancer can occur as haemoptysis from a bronchogenic cancer, haematuria from bladder cancer, vaginal bleeding from advanced gynaecological cancers or from local recurrence of breast cancer, skin metastasis from breast cancer, melanoma or head and neck cancers. Bleeding is frightening for the patient and can be significant, necessitating a blood transfusion. Other treatments used in palliative medicine include symptom controlling drugs (analgesics, antiemetics), anticancer systemic therapy (cytotoxic drugs, endocrine therapy), physical aids (crutches, walking frames) and palliative surgery (laminectomy, stents, orthopaedic surgery). Thus, the care of patients with metastatic cancer requires a multidisciplinary team just as much as the curative treatment of cancer does [23. To achieve control of physical symptoms requires: (a) Accurate diagnosis; 367 (b) (c) (d) (e) Good clinical judgement; Patient focused and individually tailored treatment; Comprehensive knowledge of cancer and its available treatment; Appropriate follow-up and reassessment. However, there is much evidence that many patients do not receive the benefit of this treatment [23. Radiotherapy may be used in more than two thirds of cancer patients in high income countries for curative intention, and for palliation when systemic therapies fail to control metastatic disease. For all countries, however, lung cancer, a partly preventable disease, is the greatest cause of cancer related deaths.

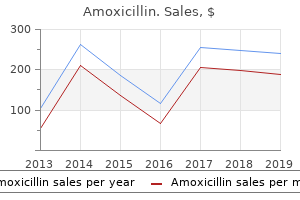

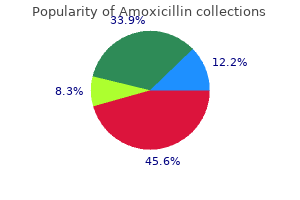

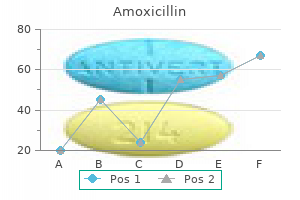

Cost and capacity analysis for three configurations of megavoltage machines: (left) two cobalt machines; (centre) two single photon energy linacs; (right) one multimodality linac. Conversely, small loads, especially those below 500 patients per year where all items are underutilized, will be associated with vastly increased costs. Such a master plan should include a realistic calculation to address the needs, equipment selection, timelines to establish the first department and to expand the provision of radiotherapy, including training of new professionals, and adequate allocation of a budget to enable efficient radiotherapy delivery and future expansion, as needed. Radiotherapy is an inexpensive solution to many cancers; it is a reproducible technique with fundamentals that rely both on a large set of evidence based medical data and on high technology equipment that has benefited from the digital revolution in the second half of the twentieth century. One characteristic of radiotherapy is its narrow therapeutic window, with cure being never very far from injury. Therefore, radiotherapy administration requires great accuracy in target volume definition and dose control. Modest underdosage leads to the recurrence of cancer, while overdosage leads to unacceptable toxicity. While more sophisticated treatment techniques have emerged recently (intensity modulation, image guidance, hadrons), equally sophisticated means to control the actual delivery of radiotherapy have been developed. Better control of dose delivery allows for better delineation between target tissue exposed to high doses and normal tissue shielded to the maximum, with steep dose gradients sometimes over a few millimetres. This, in turn, requires better volume definition and better control of patient positioning. A fundamental question in radiotherapy is what exactly needs to be irradiated, and at which dose. It is by sustained efforts, through a better knowledge of anatomy and oncological surgical techniques, that the current approach has emerged. Atlases of the natural routes of cancer spread, through lymphatic channels and anatomical planes, are now available for all parts of the human body. A picture emerges where all steps between the diagnosis of cancer until cure of the patient can be merged into a single elaborate system whose objective is the safe and appropriate delivery of radiotherapy. It is a set of control points that ensures that each element of a process or a series of processes conforms to a pre-established standard. The idea behind it is that if a process conforms to its standards, then the result will actually meet expectations. In radiotherapy, the expectations are control of a cancer with a minimal and predictable impact on the quality of life. It is indeed a requirement that radiotherapy departments question their outcome levels and benchmark them against published peer reviewed data. This is a difficult undertaking because radiotherapy is rarely the decisive intervention in cancer control. More often, it is part of a multimodal approach where the surgical or medical oncology elements escape the quality system of radiotherapy departments, while they are equally decisive in the ultimate treatment success. In addition, for survival data to be a relevant indicator, time is needed before a significant figure can be calculated. If results do not match expectations, little can be known about the underlying reasons, and what elements need to be improved for a correction of this underperformance. Last but not least, five year results actually assess the situation prevailing five years earlier. In the meantime, many elements might have changed in terms of staff, equipment or procedures. The rationale here is that quality can only be produced within an appropriate infrastructure (buildings, staffing, competencies and equipment). In most developed countries, the local health authorities accredit radiotherapy departments on the basis of the infrastructure in (b) 296 (c) place. Indeed, several examples have been published demonstrating that the absence of a minimal level of infrastructure is responsible for suboptimal cancer control. However, this approach lacks specificity, as it does not provide information on precisely what element of the infrastructure is responsible for the suboptimal performance. Clearly, norms are desirable on infrastructure details, but they say nothing about the actual utilization of competencies and equipment. Infrastructure is therefore a necessary but not sufficient condition to guarantee a service of quality. It is based on the observation that if a process conforms to a standard, then the quality of its result is predictable. This is the standard industrial approach to quality: no risk that a product will not match its quality specification can be taken (for obvious commercial reasons).

Diseases

Then, as you rotate through the different fields of medicine during the junior year, look closely at each specialist and try to discern their personality type. The overall goal is to make sure you know yourself well before determining which specialty is right for you. Introverts may become more extroverted, or thinkers might become feelers from one year to the next. Students who were sensing, thinking, and judging types chose obstetrics and gynecology. Students who were intuitive, feeling, and perceiving types undertook careers in psychiatry. Another study looked closely at the association between these two variables for medical students deciding between primary care and non-primary care specialties. Introverts and feelers were more likely to choose primary care, a highly service-oriented area of medicine with the rewards of longterm patient relationships. For graduates who chose non-primary care fields, extroverted thinkers preferred surgical specialties, which is to be expected given the nature of surgical practice-high patient volume, less long-term continuity of care, and clinical situations that require rapid decisions based on facts. Introverts and feeling types are more likely to choose primary care because of its nurturing, compassionate aspects. Within primary care, feeling types are more likely to choose family practice over internal medicine (which has a more technological focus). Sensors-who love more technological, direct approaches with well-learned skills-are more common in surgery (general and orthopedic) as well as obstetrics-gynecology. Intuitives prefer complex diagnostic challenges and problems with subtle nuances, so they are more likely to become psychiatrists. Thinking types prefer caring for patients where impartiality and stamina are required. They also flock to the surgical specialties, where rapid decisions are needed based on hard evidence and facts. Remember-the more you understand your temperament and motivations, the less likely you will allow other variables (such as those discussed in Chapter 3) to overshadow them. Simply be aware that working with people with the same personality preferences is an important variable to consider. Typically, a physician who switches to a new specialty chooses one in which his or her own personality type is much more common. After all, medicine is a wonderfully broad profession in which there is an appealing specialty for every personality type! Personality profiles and specialty choices of students from two medical school classes. New results relating the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and medical specialty choice. Choosing the ideal field of medicine requires time, research, and a great deal of thought and investigation. Whether you are a first-year or fourth-year medical student, you need to put in the time to research every specialty under consideration. Procrastination will only lead to a more stressful (and ill-informed) decision-one that may end up being the wrong specialty! This chapter addresses the potential opportunities for students to go about researching medical specialties. Use the different resources and options available to immerse yourself fully in a specific area of medicine. By interacting with other clinicians, you will find out whether that specialty makes good use of your interests, preferences, talents, and values. The list may seem daunting, but every student has 4 years in which to take advantage of the many sources of information. These are the only means by which doctors-to-be can figure out answers to many questions: What types of patients do you prefer By pursuing as many of these options as possible, medical students will better determine their needs and preferences regarding each important variable in specialty selection. This discussion is particularly beneficial for first- and second-year (preclinical) medical students. Instead, they are immersed in the rigorous demands of studying anatomy, pathology, microbiology, and other basic sciences.

T-tubules are quite distinct from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and collectively make up the T-system. The T-system rapidly transmits impulses from the exterior of the fiber to all the myofibrils throughout the cell, thereby producing a coordinated response. Passage of electrical impulses Under the electron microscope, the myofibril is seen to consist of longitudinal, fine myofilaments, of which two types have been identified, differing in size and chemical composition. The thick filaments are 10 nm in diameter; thin filaments have a diameter of only 5 nm. The midportion is smooth, whereas the ends are studded with many short projections. Myosin filaments can be dissociated into their constituent molecules, of which there are about 180 per filament, each consisting of a head and a tail. The tails of the molecules lie parallel and are so arranged that the smooth midportion of the filament consists of the tails only. The heads project laterally from the filament along its tapered ends and form a helical pattern along the filament. Most of the tail consists of light meromyosin, whereas the heads, with parts of the tails, consist of heavy meromyosin. A second protein, tropomyosin, lies within the groove between the two actin strands and gives stability to the actin filament. A protein complex consisting of three polypeptides designated as troponin-T, troponin-I, and troponin-C is bound to tropomyosin at regular intervals of 40 nm. Troponin-T binds the troponin complex to tropomyosin and positions the complex at a site on the actin filament where actin can interact with myosin. When this occurs, a conformational change occurs in the troponin complex, and myosin can now bind and interact with the actin filament. As a result of forming and breaking bonds between the myosin and actin filaments, actin filaments slide past the myosin filaments, and the length of each sarcomere is reduced, resulting in an overall shortening of each myofibril. The arrangement of the thick and thin filaments is responsible for the banded pattern on the myofibrils. The I band consists only of thin filaments, which extend in both directions from the Z line. The filaments on one side are offset from those of the other, and connecting elements appear to run obliquely across the Z line to create a zigzag pattern. As the actin filament nears the Z line, it becomes continuous with four slender threads, each of which appears to loop within the Z line and join a thread from an adjacent actin filament. Several accessory proteins (-actinin, Z protein, filamin, and amorphin) have been identified in the Z line. An additional accessory protein, nebulin, is associated with the actincontaining thin filaments. The A band consists chiefly of thick filaments (myosin) with slender cross-connections at their midpoints, which give rise to the M line. A protein, myomesin, in the region of the M line holds the myosin filaments in register and maintains a three-dimensional spacial arrangement. Another myosin-binding protein, C protein, runs parallel to the M-line in the outer region of the A band and also aids in holding the myosin myofilaments in register. Titin (connectin) is an exceptionally large accessory protein with elastic properties. The titin molecule spans the distance between the Z line and the M line and is thought to function as a molecular spring for the development of a reactive force during stretch of a non-activated muscle. Titin, together with the connective harness enveloping the skeletal muscle cell, resist forces that would pull actin filaments out from between the myosin filaments making up the A band. Recent evidence also suggests that titin may be involved in intracellular signal transduction pathways. Actin filaments extend into the A bands between the thick filaments; the extent to which they penetrate determines the width of the H band (which consists only of thick filaments) and depends on the degree of contraction of the muscle. At the ends of the A bands, where the thick and thin filaments interdigitate, the narrow space between filaments is traversed by crossbridges formed by the heads of the myosin molecules. Muscle function depends on a precise alignment of actin and myosin within each myofibril. This is achieved by accessory proteins which attach to different components of the contractile mechanism and holds them in register with each other.

It circumvents the difficulties of planning ahead and allows develop ment to proceed with a minimum of design or regulatory mechanisms. Since distant neuronal structures must engage in complex cooperative interactions in mature brains, the functional matching of cell populations and connections is particularly important. Programmed neuronal death plays a first role in this process by matching different but interconnected cell populations to one another. Some of the first evidence for the role of 196 < the Symbolic Species selective cell death in the netvous system came from studies of peripheral netves and their external connections. Normally, a significant fraction of the initial population of motor neurons is eliminated from the spinal cord. In addition, animals from which muscles or whole limbs have been experi mentally removed early in embryogenesis lose an even larger proportion of the motor neurons of the spinal cord and brain stem that would have pro jected to these peripheral structures. But in graft experiments where addi tional tissue is added to a developing embryo. Extra neurons were not initially produced, but neurons that would normally die were spared by the enlarged target (see Figure 7. Nature prefers to overproduce and trim to match, rather than carefully monitor and coordi nate the development of innumerable separate cell populations. Recent studies have begun to demonstrate that a variety of guidance mechanisms assist a growing axon in locating a target region elsewhere in the brain. Among these are guide filaments extended from non-neuronal cells, regional differences in cell-surface adhesion, spatial patterns of attraction and repulsion mole cules, mechanical properties of tissues, and specific growth factors released by cells within target regions which help support axons that have arrived at the correct destination. These mechanisms are sufficient to bias axon growth toward selected general target regions, but they are insufficiently precise to specify any but the most global target distinction. More specific con nectivity is instead specified post hoc, so to speak, as many connections be come selectively culled in response to functional processes. One reason for this lack of specificity is that the amount of information necessary to specify even a few percent of neural connections between cells would dmand incredible amounts of genetic information. Further ev idence that there must be an outside source of brain-wiring information is provided by the relative constancy of genome size across vast differences in brain size and correspondingly astronomical differences in connections. Although the human brain probably possesses hundreds or even thousands of times the number of neurons that are in some of the smallest vertebrate brains and millions of times more connections, it does not appear that this has correlated with a significant increase in genome size. But there is another constraint on the developmental process that has dictated this design strategy. In tissue culture (in vitro) experiments, where explanted cerebral cortex and thalamus (the major input nucleus) slices are allowed to grow axons into one another, there are no preferred associations between specific thalamic nuclei and cortical regions. For example, layers 3 and 5 can connect to any cortical structure (lower left); layer 5 can also project to midbrain tissue, but not to thalamus (top); and layer 6 neurons do not project to cortex, only to thalamus (top). Relationship between thal amus and midbrain is predictedfrom the other combinations and natural patterns, but has not been demonstrated by experiment. Thefigure summarizes studies from Molnar and Blakemore (1 991) and Yamamoto, et al. Since essentially identical molecu lar processes are involved in establishing the initial brain divisions in animals 198 < the Symbolic Species as different in brain size as mice and humans, the same partitioning of neural segmental divisions must be extrapolated over a vast range of sizes. Larger brains will be less able to rely on genetic mechanisms to determine struc tural differences and more prone to proportional perturbations due to ex trapolated growth processes. The added design information has to come from somewhere else in larger brains, but little of the extra information seems to come directly from genes. In the same sense that Darwinian processes have created new design information for building organisms dur ing the course of the evolution of life, Darwinian-like processes in brain de velopment are responsible for creating the new information required to adapt large brains to themselves and to their bodies. Striking evidence for the generality of the information involved in spec ifying connections in the brain comes from neural transplantation experi ments that cross species boundaries. For ex ample, it is often assumed that human brains are different because human neurons receive different genetic instructions about where to grow and where not to grow, and which cells to connect with and which not to con nect with. The chimeric brains that result from such interspecies transplantation experiments should be dysfunctional in the extreme, and the greater the species difference, the greater should be the disruption of function. So, at this level of target specification, it appears that the signals for guiding the formation of neural connections in rat and pig brains are interchangeable. Deacon > 199 A Normal connection patterns in mature rat (and pig) brains B Growth of axons from fetal pig cortex cells implanted in striatum c Growth of axons from fetal pig striatal cells implanted in striatum 0 ventral midbrain cells* dopamine cells e striatal cells e cortical cells Experiments implanting embryonic pig cells into rat brains (see also Chap ter 6, Figure 6. Even though the donor neurons are from a very different species, and are sometimes implanted in places in the brain where such neurons are not normally found, their axons are still able to use the host brain s signals to guide their growth to appropriate targets (as in A). Neural cellsfrom the embryonic cortex (B), striatum (C), and ventral mid brain (D) are shown transplanted into the striatum in separate experiments.

During its growth in the follicles, the oocyte is nourished by blood vessels of the ovary via the theca interna. When a corpus luteum is formed after ovulation, estrogens and progesterone are produced and are responsible for development of the uterine mucosa prepared for reception of the blastocyst. The periodic nature of hormone production by the ovary establishes the menstrual cycle during which, in the absence of pregnancy, the uterine mucosa is shed. If pregnancy occurs, the corpus luteum persists and its hormonal activity maintains the endometrium in a prepared state. Female reproductive function is regulated primarily by positive and negative feedback loops on neurons in the hypothalamic region of the brain and on cells (gonadotrophs) within the anterior pituitary. Follicle-stimulating hormone influences the growth of late primary and secondary follicles and promotes the formation of estrogens. The oviduct is the site of fertilization of an ovum and also transports the zygote to the uterus as the result of muscular and ciliary actions. Conditions within the oviduct sustain the zygote as it undergoes cleavage during passage through this tube. Nutrition for the zygote is provided by material stored in the cytoplasm of the ovum. On entering the uterine cavity, the blastocyst lies in secretions produced by the endometrium. The secretion is rich in glycogen, polysaccharides, and lipids, providing an excellent "culture medium" for the dividing cells of the blastocyst. The uterine endometrium, to which the blastocyst attaches, provides for the sustenance of the embryo throughout its development. A rich food supply for the implanting blastocyst comes from the secretions of the uterine glands and from products of the uterine stroma as the blastocyst burrows into the endometrium. These products are absorbed by the syncytial trophoblast and diffuse to the developing embryo. As the trophoblast continues to erode into the endometrium, blood-filled spaces form, and the blastocyst is bathed by pools of maternal blood that supply the embryo with nourishment. When a placenta has been established, the nutritional, respiratory, and excretory needs of the embryo are met by this fetal-maternal membrane. The placenta also has protective functions, preventing passage of particulate matter to the embryo. The basal layer of the endometrium is not shed at parturition or at menstruation and provides for the restoration of the uterine mucosa after these events have occurred. Changes in the secretory activities of cervical glands during the menstrual cycle may have some significance in fertility. During most of the cycle, the glands produce a thick, viscous mucus that appears to inhibit passage of sperm. The thin, less viscid mucus elaborated at midcycle appears to favor the movement of sperm into the proximal regions of the female reproductive tract. The mammary glands provide nourishment for the newborn, which is delivered in an immature and dependent state. The first secretion, colostrum, has a high content of immunoglobulins and give passive immunity to the suckling young. Passage of milk from the alveoli into the initial segments of the ducts is accomplished by contraction of myoepithelial cells under the influence of the hormone oxytocin. However, hormones also may be secreted directly into the intercellular space (paracrine secretion) to elicit a local effect on adjacent cells. In some instances cells may secrete a chemical messenger that acts on its own receptors and is self-regulatory (autocrine secretion). Hormones that are secreted into the vascular system eventually enter the tissue fluids and, depending on the specificity of the hormone, can alter the activities of just one organ or influence several. The organs that respond to a specific hormone are the target organs of that hormone. Hormones may be classified into three general categories according to their chemical structure: amino acid polymers (polypeptides, proteins, or glycoproteins), cholesterol derivatives (sterols and steroids), and tyrosine derivatives (thyroid hormones and catecholamines). Many of the peptide and protein hormones exist in the circulation in a free state unbound to other elements in the plasma. In contrast, thyroid and steroid hormones circulate in the blood bound to specific plasma carrier proteins.

Rosehips (Rose Hip). Amoxicillin.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96814

Ancient T-independence of mucosal IgX/A: Gut microbiota unaffected by larval thymectomy in Xenopus laevis. Anti-immunoglobulin M induces both B-lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation in Xenopus laevis. Oral immunization of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) upregulates the mucosal immunoglobulin IgX. Genome reannotation of the lizard Anolis carolinensis based on 14 adult and embryonic deep transcriptomes. Extensive diversification of IgD-, IgY-, and truncated IgY(deltaFc)-encoding genes in the red-eared turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Phylogeny of the immune response: studies on some physical, chemical, and serologic characteristics of antibody produced in the turtle. Frequencies of cell-surface or cytoplasmic IgM-bearing cells in the spleen, thymus and peripheral blood of the snake Elaphe quadrivirgata. Assessing humoral and cellmediated immune response in Hawaiian green turtles Chelonia mydas. Lymphocytes of the shark with differential response to phytohemagglutinin and concanavalin A. T-cell receptor gene homologs are present in the most primitive jawed vertebrates. Transplantation reactions of two species of Osteichthyes (Teleostei) from South Pacific coral reefs. Lymphocyte heterogeneity in the trout, Salmo gairdneri, defined with monoclonal antibodies to IgM. Production and characterisation of a monoclonal antibody against the thymocytes of the sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax L. Indications for a distinct putative T cell population in mucosal tissue of carp (Cyprinus carpio L). Immunodetection of lymphocyte subpopulations involved in allograft rejection in a teleost (Dicentrarchus labrax L. Yamaguchi T, Katakura F, Shitanda S, Niida Y, Toda H, Ohtani M, Yabu T, Suetake H, Moritomo T, Nakanishi T. Clonal growth of carp (Cyprinus carpio) T cells in vitro: long-term proliferation of Th2-like cells. Rhabdovirus infection induces public and private T cell responses in teleost fish. Diversity, molecular characterization and expression of T cell receptor g in a teleost fish, the sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L). In vivo allograft rejection in a bony fish Dicentrarchus labrax (L): characterisation of effector lymphocytes. In vitro generation of viralantigen dependent cytotoxic T-cells from ginbuna crucian carp Carassius auratus langsdorfii. Leopard frog (Rana pipiens) spleen lymphocyte responses to plant lectins: kinetics and carbohydrate inhibition. T-lymphocyte proportions, distribution and ontogeny, as measured by E-rosetting, nylon wool adherence, postmetamorphic thymectomy, and non-specific esterase staining. Development of T lymphocytes in Xenopus laevis: appearance of the antigen recognized by an anti-thymocyte mouse monoclonal antibody. Late thymectomy in Xenopus tadpoles reveals a population of T cells that persists through metamorphosis. Studies on T-cells of the lizard Calotes versicolor: adherent and non-adherent populations of the spleen. The effect of the seasonal cycle on the splenic leukocyte functions in the turtle Mauremys caspica. It will not cover the evolution of interferons, which is described in chapter: Antiviral Immunity: Origin and Evolution in Vertebrates, or the chemokines, which have had many recent reviews (eg, Refs. Interestingly, although there is conservation of a 12 b-sheets structure, when the chicken57 and fish ligands are modeled while interacting with their respective receptors, there is a high level of variability of positions involved in receptor binding.

It is suggested to play an important role for the fetus maintenance and development, in addition to its primary antiviral function. The two groups share low sequence-identities at the protein level, ranging from 15. At the molecular level, the teleost type I ifn genes share the same genetic organization as their amphibian and sarcopterygian (coelacanth) counterparts, and are encoded by genes with a genomic structure of 5 exons and 4 introns. In the zebrafish genome, four ifn genes have been found, with three residing in chro 3 and one in chro 12. Salmonids have all six phylogenetic subfamilies and the largest number of gene copies in the genome. The corresponding locus is also identifiable in elephant shark100 and coelacanth,103 and in some teleost species such as pufferfish, zebrafish, and Atlantic salmon. Mx genes have been reported in amphibians139 and reptiles,140 although little information regarding their functionality is available in these species. While in most species at least two Mx isoforms are present, in birds only one cytoplasmic Mx isoform exists. Furthermore, initial descriptions of duck141 and chicken142 Mx proteins reported a lack of antiviral activity. However, the high degree of polymorphisms in this gene observed in birds does suggest a role in antiviral immunity that is yet to be clarified. Recently, a viperin gene has been reported in birds179 and some other fish species. These include rainbow trout,178 goldfish,208 Atlantic salmon,209 crucian carp,210 Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua),211,212 and Japanese flounder213; all of these genes are upregulated in response to viral stimuli. In Atlantic cod, three different isoforms are present, and even though the three of them were induced in response to Poly I:C, only one of them seemed to conjugate with intracellular proteins, suggesting different functionalities for each isoform. Several trim genes have been identified in birds,217 amphibians,218 fish, and even nematodes. On the other hand, while orthologues of some mammalian trim genes such as trim5, trim22, or trim19 are clearly missing from fish genomes, what appear to be true counterparts of mammalian trim genes have also been reported in fish. This system, conserved throughout vertebrate evolution, seems particularly important to vertebrates in which an adaptive immune system is not fully developed and/or is dependent on environmental parameters such as temperature. The authors want to thank Professor Chris Secombes for critically reviewing this chapter. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on toll-like receptors. Regulation of cellular gene expression by interferon-gamma: involvement of multiple pathways. Reading the viral signature by toll-like receptors and other pattern recognition receptors. Evolution of host innate defence: insights from Caenorhabditis elegans and primitive invertebrates. Ligand specificities of toll-like receptors in fish: indications from infection studies. Molecular cloning and characterization of toll-like receptor 3 in Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Genomic organization and expression analysis of toll-like receptor 3 in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Positive selection pressure within teleost toll-like receptors tlr21 and tlr22 subfamilies and their response to temperature stress and microbial components in zebrafish. Evolution of the chicken toll-like receptor gene family: a story of gene gain and gene loss. Prediction of the prototype of the human toll-like receptor gene family from the pufferfish, Fugu rubripes, genome. Molecular cloning and characterization of toll-like receptor 9 in Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Novel interferon delta genes in mammals: cloning of one gene from the sheep, two genes expressed by the horse conceptus and discovery of related sequences in several taxa by genomic database screening. Interferonepsilon protects the female reproductive tract from viral and bacterial infection.

The blood then slowly seeps through the red pulp and finds its way into the venous system through the walls of the splenic sinusoids. The closed circulation theory holds that the capillaries open directly into the lumina of the venous sinusoids; blood enters the sinusoid at the capillary end and leaves at the venous end because of a decreasing pressure gradient between the two ends of the sinusoid. A compromise between the two views suggests that a closed circulation in a contracted spleen becomes open when the spleen is distended. Splenic sinusoids drain into pulp veins, which are supported by a thin muscle coat and, more externally, are surrounded by reticular and elastic fibers. A sphincter-like activity of the smooth muscle has been described at the junction of the pulp veins and sinusoids. Pulp veins enter trabeculae, where, as trabecular veins, they pass in company with the artery. Thymus the thymus is a bilobed, encapsulated lymphatic organ situated in the superior mediastinum dorsal to the sternum and anterior to the great vessels that emerge from the heart. The thymus is the only primary lymphatic organ and is the first organ of the embryo to become lymphoid. Unlike the spleen and lymph nodes, it is well developed and relatively large at birth. The greatest weight (30 to 40 g) is achieved at puberty, after which the organ undergoes progressive involution and is partially replaced by fat and connective tissue. Each lobe arises from a separate primordium, and there is no continuity of thymic tissue from one lobe to the other. A thin capsule of loosely woven connective tissue surrounds each lobe and provides septa that extend into the thymus, subdividing each lobe into a number of irregular lobules. In the usual sections, the medulla may appear as isolated, pale areas completely surrounded by denser cortical tissue. However, serial sections show that the lobules are not isolated by the septa; the medullary areas are continuous with one another throughout each lobule. The free cells of the thymus are contained within the meshes of a reticular network, which, however, differs from that of other lymphatic tissues. In the thymus the reticular cells take origin from endoderm rather than mesenchyme and are not associated with reticular fibers. These epithelial reticular cells are stellate in shape with greatly branched cytoplasm that contains few organelles. The large, round or oval euchromatic nuclei show one or more small but prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasmic processes are in contact with the processes of other reticular cells and at their points of contact are united by desmosomes. The spleen has no afferent lymphatics, but efferents arise deep in the white pulp and converge on the central arteries. The lymphatics enter trabeculae and form large vessels that leave at the 142 Thus, the stroma of the thymus consists of a cytoreticulum composed of epithelial cells. Often, however, in histologic sections it appears to be isolated within a lobule, surrounded by a complete layer of cortex. Lymphocytes are less numerous than in the cortex, and the epithelial reticular cells are not as widely dispersed or as highly branched. The reticular cells tend to be pleomorphic and vary from stellate cells with long processes to rounded or flattened cells with many desmosomes and abundant tonofilaments. Dendritic interdigitating cells are found in the medulla and corticomedullary region. The free cells of the medulla are mainly small lymphocytes, but a small and variable number of macrophages are present. Collagen and reticular fibers extend for short distances from blood vessels and wind between the epithelial cells. Rounded or ovoid epithelial structures, the thymic corpuscles, are a prominent feature of the medulla.

Learning even a simple symbol system demands an approach that postpones commitment to the most immediately obvious associations until after some of the less obvious distributed relationships are acquired. Only by shifting attention away from the details of word-object relationships is one likely to notice the existence of superordinate patterns of combinatorial relationships between symbols, and only if these are sufficiently salient is one likely to recognize the buried logic of indirect correlations and shift from a direct indexical mnemonic strategy to an indirect symbolic one. In this way, symbol learning in general has many features that are simi lar to the problem of leaming the complex and indirect statistical architec ture of syntax. This parallel is hardly a coincidence, because grammar and syntax inherit the constraints implicit in the logic of symbol-symbol rela tionships. These are not, in fact, separate learning problems, because sys tematic syntactic regularities are essential to ease the discovery of the combinatorial logic underlying symbols. The initial stages of the symbolic shift in mnemonic strategies almost certainly would be more counterintu itive for a quick learner, who learns the details easily, than for a somewhat impaired learner, who gets the big picture but seems to lose track of the details. In general, then, the initial shift to reliance on symbolic relation ships, especially in a species lacking other symbol-learning supports, would be most likely to succeed ifthe process could be shifted to as young an age as possible. The evolution of symbolic communication systems has there fore probably been under selection for early acquisition from the beginning of their appearance in hominid communication. So it is no surprise that the optimal time for beginning to discover grammatical and syntactic regular ities in language is also when symbolic reference is first discovered. How ever, the very advantages that immature brains enjoy in their ability to make the shift from indexical to symbolic referential strategies also limit the de tail and complexity of what can be learned. Learning the details becomes possible with a maturing brain, but one that is less spontaneously open to such "insights. How do sym bolic systems evolve structures that are both capable of being learned and yet capable of being highly complex And how have human learning and 136 < the Symbolic Species language-use predispositions evolved to support these two apparently con trary demands Consequently, strong social selection forces will act on language reg ularities to reduce the age at which they can begin to be learned. Languages may thus be more diffi cult to learn later in life only because they evolved to be easier to learn when immature. So immaturity itself may provide part of the answer to the paradoxical time-limited advantage for language learning that Kanzi demonstrates. But equally important is the fact that both the lexigram training paradigms used with his mother and the structure of English syntax itself had evolved in response to the difficulties this imposes, an q so had spontaneously become more conducive to the learning patterns of immature minds. The existence of a critical period for language learn ing is instead the expression of the advantageous limitations of an imma ture nervous system for the kind of learning problem that language poses. Deacon > 137 And language poses the problem this way because it has specifically evolved to take advantage of what immaturity provides naturally. Nat being exposed to language while young deprives one of these learning advantages and makes both symbolic and syntactic learning far more difficult. Though older animals and children may be more cooperative, more attentive, have bet ter memories, and in general may be better learners of many things than are toddlers, they gain these advantages at the expense of symbolic and syn tactic learning predispositions. This is demonstrated by many celebrated "feral" children who, over the years, have been discovered after they grew up isolated from normal human discourse. Their persistent language limi tations attest not to the turning off of a special language instinct but to the waning of a nonspecific language-learning bias. This may also be responsible for another curiously biased language phe nomenon that linguists have taken as evidence for innate knowledge of lan guage structure: the transition from pidgin languages to creole languages. Pidgins are forced hybrids of languages that have arisen in response to the "collision" of languages, typically arising as a result of colonization or trade relationships. They are not the primary language of anyone and often have enjoyed a very transient history, typically disappearing within a generation or so. They are like makeshift collections of language fragments from both languages that are used as a common translation bridge that is mutually un derstandable. But during recorded history, a number of populations have also evolved new languages directly from pidgins, which differ from either "parent" language. Such "creole" languages appear to be able to originate quite rapidly-within as little as one or two generations-especially when a population finds itself transported and isolated in a new context, such as periodically occurred as a result of the slave trade of the past few centuries.

References: